Economics and Game Theory

The mathematics of making everybody happy.

In general, an equilibrium in a game (game theory) or auction (economics) is reached if each participating player or bidder conciders the outcome as most beneficial for their own (selfish) good compared to the possible alterntives. Mathematically, this can take various forms depending on the mathematical formulation of the problem, as well as the assumptions and variables that are taken into account. I have worked on two different projects involving concepts of equilibria. In both cases we relate the concept of equilibrium with polyhedral geometry.

Competitive Equilibrium in Economics

A combinatorial auction is an auction in which the price and distribution of multiple goods are decided simultatiously within an instant. In the setting of graphical valuations, each bidder tells the auctioneer beforehands how much they would be willing to pay for an item of each type, as well as discounts and fees for each pair. This valuation is controlled by a graph \(G\), for which weights on the vertices and edges define the bidders’ valuation for each subset of goods. Given these valuations, the auctioneer decides a price per item and a distribution of the goods among the bidders.

A bidder is happy with the outcome of an aution, if they receive a subset of goods at a price which maximizes their surplus. We pose the question of the existence of a price and an allocation, at which all bidders are happy; this is a competitive equilibrium. Pushing this further, we ask the following.

Is a competitive equilibrium guarenteed to exist, meaning that we can always find a price and distribution to make everybody happy, regardless of the bidders’ own preferences?

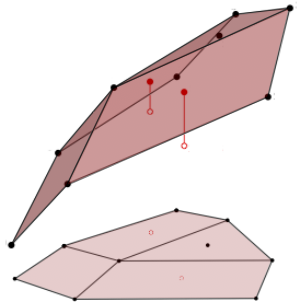

We translate the question of the (guaranteed) existence of a competitive equilibrium to a condition on lattice points in the Minkowski sum of faces of a certain polytope \(P(G)\). This condition can be viewed as a generalization of the Integer Decomposition Property of lattice polytopes. In the case of the complete graph, the polytope turns out to be the correlation polytope, a polytope which is isomorphic to the cut polytope (however, this is not a lattice-isomorphism).

In the case of the complete graph, every bidder is asked for their bid with regards to every single item and every pair of items. We show that in this case the condition on the correlation polytope can always be satisfied, thus implying that a competitive equilibrium is always guaranteed to exist.

Furthermore, we show that this condition is not always satisfied by providing examples of graphs for which a competitive equilibrium is not guaranteed to exist.

Slides of Talks

| 5 October 2022 | MOR Seminar at University of Twente | [Slides] |

| 4 July 2022 | Discrete Math Days | [Slides] |

| 16 March 2022 | DM/G-Seminar at TU Berlin | [Slides] |

| 4 March 2022 | Mini-Symposium on Lattice Polytopes | [Slides] |

References

Correlated Equilibrium in Game Theory

The most famous equilibrium concept in game theory is the notion of Nash Equilbrium. This has been extensively studied since the 1950’s, and it is known that the set of Nash equilibria of a fixed game can be arbitrarily complicated: in fact, a universality statement holds, saying that every (arbitrarily complicated) semialgebraic set can appear as the set of Nash equilibria of some game. At the same time, Nash equilibria assume that the choices of all players are made independenlty – a feature which is arguably only the case in very special instances.

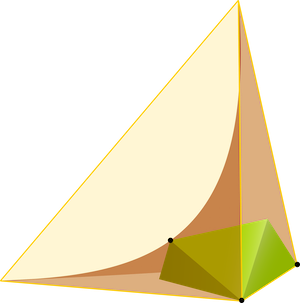

A more general concept is the notion of Correlated Equilibrium, a notion which assumes that there exists some external device which gives a recommendation to all players, modelling a relation between their choices. The set of correlated equilibria of a fixed game is described by a linear program. That is, the set of such equilibria is given as the set of solutions of finitely many linear inequalities, and the set of solutions thus forms the Correlated Equilibrium Polytope of the game. The Nash equilibria of the game turn out to be the intersection of this polytope with the Segre variety inside the probability simplex. Below is a 3d model of the correlated equilibrium polytope (blue) inside the probability simplex (yellow) the Segre embedding of \(\mathbb{P}^1 \times \mathbb{P}^1\) (orange), and the Nash equilibria (green).

The question that motivates us is the following.

Which combinatorial types of polytopes can arise as a correlated equilibrium polytope of a \((d_1 \times \dots \times d_n)\)–game of \(n\) players, where each player has a fixed number of \(d_i\) strategies?

In fact, it is not even known under which circumstances the correlated equiblibrium polytope attains which dimension. We study the Region of full-dimensionality, a semialgebriac set which describes the conditions for the polytope to be of maximal dimension. Furthermore, we investigate certain oriented matroid strata. Restricting the strata to a linear subspace allows us to investigate the possible combinatorial types that can appear for small games.

References

- Combinatorics of Correlated Equilibria Experimental Mathematics, April 2024. [abstract] [doi] [supplementary material] [bibtex]